Africa’s Minerals and the Global Clean-Tech Race: Beyond Extraction to Industrial Strategy

Africa’s minerals are no longer peripheral to the global economy. They now sit at the centre of the clean-technology transition that will define industrial power in the twenty-first century.

Lithium, cobalt, copper, manganese, graphite, and rare earths are not abstract commodities. They are the physical foundations of batteries, electric vehicles, grids, wind turbines, and energy storage systems.

As governments race to decarbonise and secure supply chains, Africa’s geological endowment has become strategic leverage. Diplomatic visits have multiplied. Infrastructure deals have accelerated, and the language of “partnership” has returned to centre stage.

But history cautions against mistaking attention for transformation.

Africa has experienced similar moments before, when global demand surged, capital arrived, and extraction expanded without structural change following. The clean-tech race risks repeating that pattern under greener branding.

The question is no longer whether Africa matters to the transition. It is whether Africa captures lasting value from it.

The New Clean-Tech Scramble

The scale of the global clean-technology build-out is unprecedented. According to the International Energy Agency, demand for critical minerals is expected to increase several times by 2030 under net-zero scenarios, primarily driven by the growth of batteries, electric mobility, and grid expansion.

Africa is central to this picture. The Democratic Republic of Congo dominates the cobalt supply. Zambia is essential to copper. South Africa anchors platinum-group metals, while Namibia and Zimbabwe are emerging lithium frontiers.

This concentration has triggered a new scramble quieter than the oil booms of the past, but no less consequential. Governments now speak of “resilience”, “friend-shoring”, and “diversification”, but the underlying imperative is control.

China recognised this early. Over the past decade, it has invested not only in extraction, but in processing, logistics, and downstream integration, embedding African minerals within broader industrial strategies.

Global North governments are now responding, often framing engagement as values-based or developmental. Yet urgency has narrowed the policy imagination. Security of supply increasingly trumps development of capability.

Africa risks being positioned once again as the solution to other people’s industrial problems.

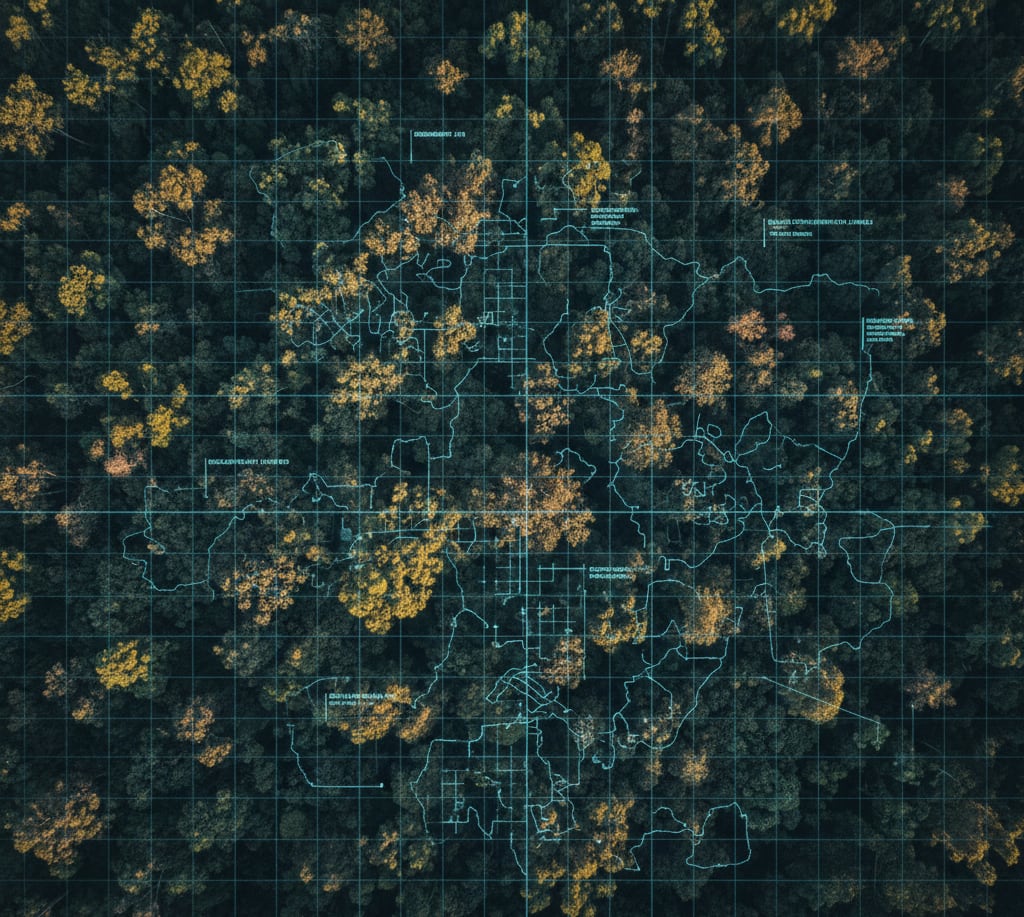

Corridors Are Not Neutral Infrastructure

Mineral corridors; railways, ports, power lines, water systems, are often presented as neutral enablers of development. In reality, they are political and economic choices that lock in outcomes for decades.

A corridor designed solely to move ore quickly to export terminals concentrates value elsewhere. A corridor designed to anchor processing and manufacturing creates domestic capabilities.

The difference lies not in engineering, but in intent.

Across the continent, corridor projects are being negotiated at speed, often under pressure from external timelines and geopolitical competition. In such contexts, long-term value creation is easily subordinated to near-term access.

As Energy Transition Africa has argued previously, the danger is not competition itself, but asymmetry, where Africa exports raw materials while importing finished clean-energy technologies at a premium.

That pattern is extractivism by another name.

If corridors are not governed deliberately, they will reproduce familiar outcomes only faster, and with fewer second chances.

Why Extraction Alone Is No Longer a Development Strategy

In the fossil-fuel era, extraction delivered revenue without transformation. In the clean-tech era, extraction alone delivers even less.

The majority of value in clean-energy supply chains is captured after mining, in refining, cathode and anode production, cell manufacturing, assembly, and system integration. These stages concentrate skills, intellectual property, and political leverage.

Countries that control them shape markets. Countries that do not remain price-takers.

For Africa, staying upstream means exposure to volatility without insulation. It means limited employment creation, shallow industrial learning, and persistent dependence on imported technologies.

It also means a paradox: supplying the materials for the global energy transition while importing the systems required for domestic energy security.

Extraction without an industrial strategy is no longer just a missed opportunity. It is a strategic vulnerability.

The Industrial Strategy Gap

The core constraint facing Africa’s minerals sector is not geological potential, but the absence of a coherent industrial strategy.

Most mineral policies remain focused on licensing regimes, royalty structures, and export volumes. Far fewer are embedded within plans that link minerals to energy supply, manufacturing, skills development, and regional markets.

Where beneficiation requirements exist, they are often undermined by unreliable power, limited infrastructure, and fragmented finance. Smelters and processing plants cannot operate without energy systems designed for industry.

This is not a failure of ambition. It is a failure of coordination.

Industrial policy is difficult. It demands patience, political discipline, and cross-ministerial coherence. But without it, mineral wealth rarely translates into industrial capability.

Africa’s clean-tech moment will be lost if minerals policy remains isolated from broader economic strategy.

Energy, Power, and Processing Must Converge

Mineral beneficiation is energy-intensive. Refineries, smelters, and processing facilities require reliable, affordable power, often at a scale and consistency many African grids struggle to provide.

This makes the convergence of energy planning and minerals strategy unavoidable.

Renewable energy offers an opportunity here. Solar, wind, and hydro can underpin processing hubs if deployed deliberately. And hybrid systems, storage, and dedicated generation can stabilise supply where national grids remain weak.

But this requires planning beyond extraction sites. Power corridors must be designed not only to serve mines, but to anchor industrial ecosystems.

Energy strategies that ignore mineral industrialisation squander leverage. And mineral strategies that ignore power realities are destined to stall.

The Role of Regional Markets and AfCFTA

No single African country can capture the entire clean-tech value chain. But the continent collectively can.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) offers a framework to distribute value creation across borders, allowing processing, manufacturing, and markets to complement rather than compete.

This requires harmonised standards, coordinated infrastructure, and shared industrial priorities. It also requires political willingness to think beyond national silos.

Negotiating mineral deals as 54 separate markets weakens Africa’s position. Coordinating as a continental bloc strengthens it.

Without regional integration, Africa risks fragmenting its leverage and being priced accordingly.

Finance: The Quiet Constraint on Industrialisation

Industrial strategy without finance is an aspiration. Yet much of the capital flowing into Africa’s minerals sector remains short-term, extractive, and risk-averse.

Public development banks, pension funds, and sovereign institutions hold substantial domestic capital. But it is rarely mobilised at scale for mineral-linked industrial infrastructure.

Foreign capital, meanwhile, prioritises security of supply over domestic capability.

As Energy Transition Africa has argued elsewhere, Africa’s transition will not fail for lack of money, but for lack of mobilisation, risk-sharing, and institutional confidence.

Without patient capital and deliberate financial architecture, beneficiation remains rhetorical.

Choosing Partners Without Choosing Sides

Africa’s mineral wealth has become entangled in global rivalry, often framed as a binary choice between China and the West. But that framing is misleading, because Africa’s interest lies not in choosing sides, but in choosing terms.

The continent can engage multiple partners on infrastructure, finance, technology, and markets if it negotiates from a position of clarity and confidence. Multipolar engagement is a strength when priorities are explicit.

But without a strategy, competition between external actors becomes competition over Africa, not competition for Africa’s development.

Agency is not automatic. It must be exercised.

From Resource Theatre to Strategy

The clean-tech race has turned minerals into geopolitics. For Africa, this creates risk and opportunity.

The opportunity lies in moving decisively beyond extraction toward industrial strategy:

- linking minerals to energy planning,

- embedding local processing requirements,

- investing in skills and technology,

- coordinating regionally,

- and mobilising domestic capital alongside foreign investment.

If these questions are not answered up front, they will be answered by default, often elsewhere.

The Decade That Decides

The next ten years will lock in supply chains, infrastructure, and alliances for generations.

Africa’s decisions now will determine whether it becomes a supplier of inputs, a consumer of technologies, or a co-architect of the global clean-energy system.

The minerals are already here. The demand is undeniable.

What remains uncertain is whether Africa will convert this moment into strategy or allow history to repeat itself under a green banner.

In the clean-tech race, Africa is no longer peripheral.

The only question is whether it negotiates as a subject, or remains an object.

Expert Analysis, Directly to You

Join our community of experts and decision-makers. Stay informed with our weekly deep dives into Africa's energy future.

Weekly briefing. Expert insights.

No spam. No generic fluff.

About the author

energytransitionafricaContributor at Energy Transition Africa, focusing on the future of energy across the continent.