Minerals Corridors in Africa: Climate, Infrastructure & Energy Transition (2026)

For much of modern history, Africa’s mineral wealth was treated as a geological inevitability rather than a strategic asset. Copper left the continent as ore. Cobalt moved raw across oceans. Value was created elsewhere, while Africa absorbed the environmental and social cost.

That era is now coming to an end, not because history has been resolved, but because the global energy transition has transformed minerals into a geopolitical currency.

Lithium, cobalt, copper, manganese, nickel, and graphite are no longer niche commodities. They are the backbone of electric vehicles, batteries, grids, and renewable energy systems. And Africa holds a significant share of them.

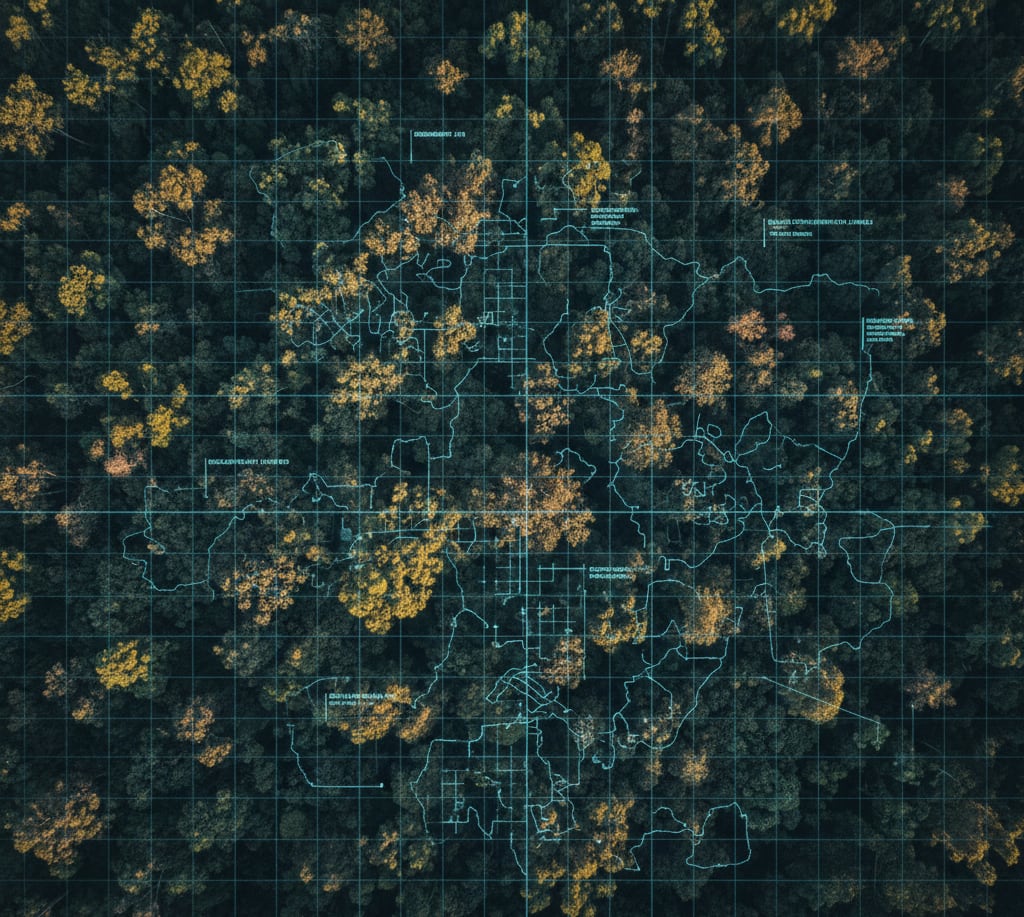

As a result, the railways, ports, roads, power lines, and water systems that move these minerals, known as minerals corridors, have become strategic infrastructure. They are no longer development projects. They are now climate battlegrounds.

What Are “Mineral Corridors” in Africa?

Mineral corridors are integrated transport and infrastructure networks (roads, rail, ports) that move critical minerals from mines to processing facilities and export hubs. These corridors are essential for clean energy supply chains but can have environmental and climate impacts if not planned sustainably.

At the centre of this shift sits the Lobito Corridor, stretching from the copper belts of the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia to Angola’s Atlantic port. What is being built there isn't simply a logistics route, but a test of who sets the terms of Africa’s participation in the global energy transition.

From Development Aid to Strategic Alignment

The renewed interest in the Lobito Corridor reflects a broader realignment in Western engagement with Africa.

For the United States and Europe, mineral corridors are now framed explicitly as tools to secure supply chains, reduce dependence on China, and “de-risk” the clean energy transition. Development finance, export credit, and diplomatic capital are being bundled together with unusual speed.

The language has shifted. Aid is no longer justified primarily by poverty reduction or growth, but by strategic necessity.

China, by contrast, arrived earlier and stayed longer. Over two decades, Chinese firms invested heavily across African mining, processing, rail, and port infrastructure, often accepting longer time horizons and lower short-term returns in exchange for control over logistics and refining capacity.

According to the International Energy Agency, global supply chains for critical minerals are dangerously concentrated, particularly at the processing stage. China currently controls between 60 and 80 percent of global refining capacity for several battery minerals.

Western re-engagement is therefore not a reset. It is a catch-up strategy. And the danger for Africa is not that interest has arrived too late, but that it arrives on terms defined elsewhere.

Corridors Lock in Development Choices

Mineral corridors are often presented as neutral, technical infrastructure: rail lines that reduce costs, ports that improve efficiency, and roads that enable trade.

In reality, corridors lock in political and economic choices for generations, and determine:

- where minerals are processed,

- who owns logistics and data,

- where skilled jobs emerge.

- which regions industrialise and which remain extractive zones.

A corridor designed purely to accelerate exports does not enable development; instead, it accelerates extraction.

The Lobito Corridor will shape the next phase of Central and Southern Africa’s mining economy. Whether it becomes a pathway to industrialisation or a faster conveyor belt for raw exports depends on choices being made now, not after construction is complete.

The Costs That Rarely Make the Press Release

Corridors are rarely empty spaces. They pass through communities, farmland, water basins, and fragile ecosystems.

Mining-linked infrastructure places intense pressure on local water systems, electricity supply, and land access. Processing facilities draw heavily on water in already stressed regions. Rail and road development fragments agricultural land. Power is often diverted to industry while households and clinics remain underserved.

Community displacement is not an accident of corridor development. It is a recurring feature.

Yet these costs are often treated as “local issues” rather than strategic risks. Social conflict, water scarcity, and energy stress undermine the very stability that investors claim to seek.

As we have previously argued, infrastructure without social legitimacy is not resilient infrastructure.

The Value Capture Question

The central issue in minerals corridors is not access to capital or technology; it is value capture.

If Africa continues to export raw lithium, cobalt, and copper while importing batteries, storage systems, and electric vehicles, the energy transition will reproduce the extractive model of the past only under a green label.

We examined this risk in detail in our analysis of Africa’s transition minerals economy, which showed that value creation remains overwhelmingly concentrated outside the continent.

Corridors that fail to embed processing, manufacturing, and skills development lock African economies into low-value positions in a rapidly growing global market.

This outcome is not inevitable, but it becomes inevitable when strategy is absent.

An Africa-First Terms Sheet for Minerals Corridors

If minerals corridors are to serve Africa’s long-term interests, they must be governed differently.

An Africa-First Terms Sheet should underpin all major corridor agreements. At a minimum, it should include four non-negotiable elements.

1. Enforceable Local Processing Requirements

Corridor access should be tied to graduated local processing thresholds defined in contracts, monitored publicly, and enforced over time.

Raw exports may dominate early phases, but refining and intermediate processing must be embedded into corridor economics from the outset. Without this, industrialisation remains rhetorical.

2. Power, Water, and Transport Co-Investment

Mining corridors cannot operate in isolation from surrounding communities.

Investors and development partners should co-invest in:

- local power generation and grid reinforcement,

- water infrastructure that serves both industry and households,

- transport links that enable regional trade, not only exports.

As our analysis of Africa’s energy crisis has shown, diverting power to industry while clinics remain dark is a political failure, not a technical one.

3. Community Benefit and Accountability Clauses

Communities should not rely on voluntary corporate social responsibility.

Employment targets, revenue-sharing mechanisms, social infrastructure commitments, and grievance processes must be contractually defined and independently monitored. Transparency is essential.

4. Regional Coordination

Mineral corridors cross borders. Negotiating them as isolated national projects weakens leverage.

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) provides a framework for coordinating standards, processing hubs, and industrial policy if governments choose to use it.

Without coordination, Africa negotiates as 54 markets. With it, as one.

Choosing Terms, Not Sides

Africa’s mistake would be to frame this moment as a binary choice between China and the West.

That framing benefits external powers, not African development.

Africa’s interest lies in choosing terms, not sides, working with different partners at different stages of the value chain, while retaining strategic control over infrastructure and outcomes.

Multipolar engagement can be an advantage. But only when African priorities are explicit, enforced, and aligned across sectors.

The Decade That Will Define the Transition

The mineral corridors built in the next ten years will shape Africa’s economic geography for decades.

They will determine whether the continent becomes:

- a supplier of raw inputs,

- a consumer of imported green technologies,

- or a co-architect of the global energy system.

The energy transition has turned infrastructure into geopolitics. Africa’s minerals are now central to global climate outcomes.

What remains uncertain is whether Africa will convert this moment into leverage or allow history to repeat itself under a greener name.

“In the energy transition, Africa’s minerals are not just assets. They are negotiating power. Whether that power is used is a political choice.”