|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

For most of modern economic history, electricity demand has followed growth. When economies expanded, electricity use rose steadily and predictably, rarely faster. That relationship is now breaking.

According to the International Energy Agency’s latest electricity forecast 2026, the world has entered what it calls the Age of Electricity, a period in which electricity demand is no longer merely keeping pace with economic growth, but outpacing it. This is a profound shift, and one that is still poorly understood outside specialist energy circles.

Between 2026 and 2030, global electricity demand is projected to grow at an average of 3.6% per year, around 50% faster than the average of the past decade. For the first time in three decades, excluding crisis years, electricity demand has begun to grow faster than global GDP. Electricity consumption is now expected to grow at least 2.5 times faster than total energy demand over the remainder of the decade.

This signals a structural transformation in how the global economy functions, and it carries especially serious implications for Africa.

What the “Age of Electricity” actually means

The IEA’s use of the term Age of Electricity is deliberate. It marks a departure from an energy system historically dominated by fuels, coal, oil, and gas, towards one increasingly organised around electrons.

Electricity is no longer just a delivery mechanism for energy. It is becoming the primary platform for economic activity. The fastest-growing segments of global economies, data centres, artificial intelligence, electric vehicles, advanced manufacturing, cooling, and digital services, are all electricity-intensive by design.

In the past, electrification was incremental. Efficiency gains often offset new demand, and in many advanced economies, electricity consumption stagnated or even declined for over a decade. That era is over.

The IEA shows that electricity demand is now rising across all major regions and sectors. Advanced economies, after fifteen years of near stagnation, are once again seeing sustained growth in power consumption, driven largely by digital infrastructure and re-industrialisation. Emerging economies continue to account for the bulk of absolute growth, but the nature of that growth has changed.

Electricity is no longer a secondary input, but is becoming the backbone of economic competitiveness.

Why this cycle is different from past electrification waves

Previous periods of electrification, from early industrialisation to post-war expansion, were supply-led. Power systems expanded to meet clearly defined industrial and household needs. Demand followed income, population growth, and urbanisation.

The current cycle is fundamentally different in three ways:

First, electricity demand is now being driven by new categories of load that didn’t exist at scale even a decade ago. Data centres alone are expected to account for roughly half of the growth in electricity demand in the United States through 2030. Cooling demand, driven by rising temperatures and urbanisation, is becoming a major structural load across Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Africa.

Second, electricity demand is becoming less elastic. Digital economies, automated manufacturing, and electrified transport require continuous, high-quality power. Outages and voltage instability are no longer inconveniences; they are binding economic constraints.

Third, the electricity system itself has become more complex. Variable renewables, decentralised generation, storage, and new demand patterns have shifted the focus from generation capacity to grids, flexibility, and system operation. The IEA identifies grid infrastructure as the primary bottleneck of the energy transition, with more than 2,500 GW of projects globally stuck in connection queues. In short, this is a reordering of the global economy around power systems.

The global picture: growth, grids, and limits

Globally, the supply response to rising electricity demand is substantial, but far from uniform. According to the IEA, renewables and nuclear are on track to account for around half of global electricity generation by 2030, marking a decisive shift in the composition of power systems. Solar photovoltaics sit at the centre of this transformation, adding more than 600 terawatt-hours of generation every year through the end of the decade, more than the current annual electricity consumption of many mid-sized economies.

Nuclear power, long written off in parts of the world, is also experiencing a resurgence. The IEA projects global nuclear generation reaching record levels by 2030, driven primarily by new capacity and life extensions in China, India, and other parts of Asia. In these systems, nuclear is being repositioned as a firm, low-carbon backbone capable of supporting rising electricity demand alongside variable renewables.

Yet the report is careful not to oversell the pace of displacement. Fossil fuels didn’t disappear. Coal remains the single largest source of electricity globally in 2030, even as its share declines. Gas-fired generation continues to grow in key markets, particularly where it plays a balancing role for renewables or supports industrial and peak demand. The transition, in other words, is additive before it is substitutive.

What makes this moment different and more consequential is the IEA’s clear conclusion that generation is no longer the main constraint on electricity systems. Across regions, the binding limits are now found elsewhere: in transmission networks that cannot move power to where it is needed, in regulatory frameworks that delay connections, and in systems that lack the flexibility to absorb new demand and variable supply.

The scale of the challenge is striking. The IEA electricity forecast estimates that more than 2,500 gigawatts of generation, storage, and large-load projects are currently stuck in grid connection queues globally. To keep pace with rising demand alone, not to accelerate decarbonisation, annual investment in electricity grids must rise by around 50% by 2030, from roughly USD 400 billion today.

This reframing matters enormously for Africa. It signals that the Age of Electricity will be won or lost not on the availability of technology, but on the strength of power systems.

Africa and the Age of Electricity: the uncomfortable divergence

Africa appears only briefly in the IEA’s electricity forecast, but the implications for the continent are stark and unsettling.

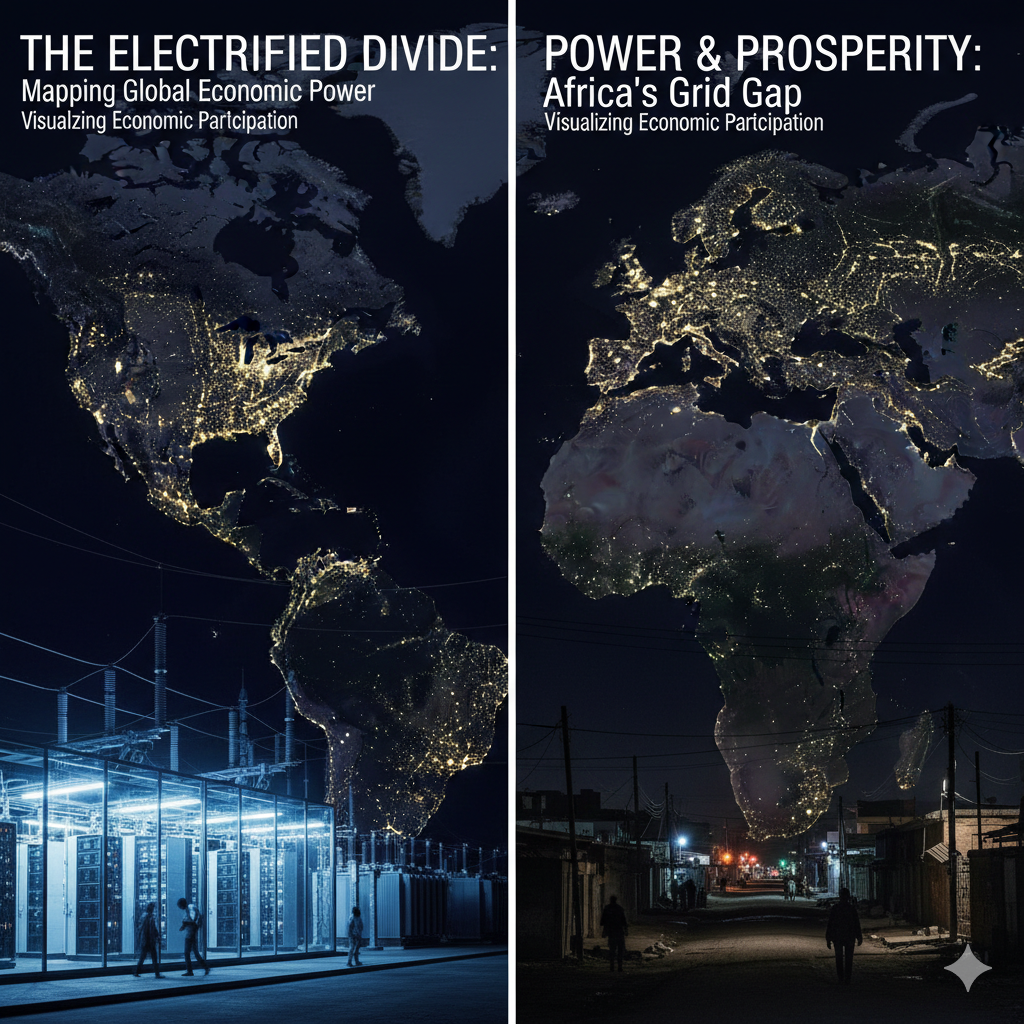

While global electricity demand accelerates across advanced and emerging economies alike, Africa risks being left outside the Age of Electricity altogether. The divergence is structural.

Per capita electricity consumption in sub-Saharan Africa has remained largely flat for around three decades, despite population growth, urbanisation, and modest gains in access. Today, the region accounts for a small fraction of global electricity demand, even as it is home to one of the fastest-growing populations in the world. Around 600 million people still lack access to electricity, and millions more who are counted as “connected” experience frequent outages, load-shedding, and poor-quality supply.

This reality exposes a deeper problem. Africa is not simply under-electrified; it is excluded from the electricity-driven growth model now shaping the global economy. While other regions prepare their grids for data centres, electric vehicles, and the digital industry, much of Africa remains preoccupied with keeping lights on at a basic level.

The IEA’s analysis implicitly challenges a long-standing assumption in development discourse: that access alone is sufficient. In a world where electricity underpins productivity and competitiveness, the quality, reliability, and scale of supply matter far more than headline connection statistics.

Measured by access alone, Africa can be portrayed as making steady progress. Measured by system capability, it is falling further behind.

Why this matters for Africa’s growth model

Africa’s economic ambitions, industrialisation, mineral beneficiation, digital services, and job creation are all electricity-intensive. Yet Africa’s power systems remain weak, fragmented, and financially constrained. Utilities struggle with high losses, politically suppressed tariffs, and chronic underinvestment. Transmission networks are thin, ageing, or incomplete. Regional power trade remains limited, not for lack of plans, but for lack of system readiness.

The IEA’s emphasis on grids and flexibility highlights the core problem. Africa’s challenge is not primarily a shortage of renewable resources or generation technology. It is the absence of robust transmission networks, solvent utilities, cost-reflective tariffs, and modern system operation.

Without these foundations, the continent cannot absorb large-scale renewables, electrify industry, or sustain energy-intensive value chains such as mineral processing and digital services. In the Age of Electricity, this is not merely an energy sector issue. It is a macroeconomic liability.

Electricity failure is no longer a social inconvenience. It is a constraint on productivity, competitiveness, and fiscal stability.

A new form of energy marginalisation

Perhaps the most important implication of the IEA’s electricity forecast is this: electricity is becoming the currency of growth.

As advanced and emerging economies invest heavily in grids to support AI, electric mobility, and the digital industry, countries with weak power systems fall further behind, regardless of their climate ambitions or resource endowments.

For Africa, this creates a risk of a new kind of marginalisation. Not one driven by a lack of fuel, but by underpowered systems.

Unless African governments prioritise grid investment, utility reform, and reliability alongside access, the continent will struggle to participate meaningfully in the next phase of global growth.

Conclusion

The IEA’s Electricity 2026 report is more than a forecast. It is a warning.

The world is reorganising itself around electricity. Economies with strong, flexible, and reliable power systems will gain productivity, resilience, and competitive advantage. Those without them will face higher costs, constrained growth, and missed opportunities.

For Africa, the Age of Electricity isn’t guaranteed. It won’t arrive through access targets alone. It must be built deliberately, urgently, and system by system.

That is the challenge the report places before the continent.