|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

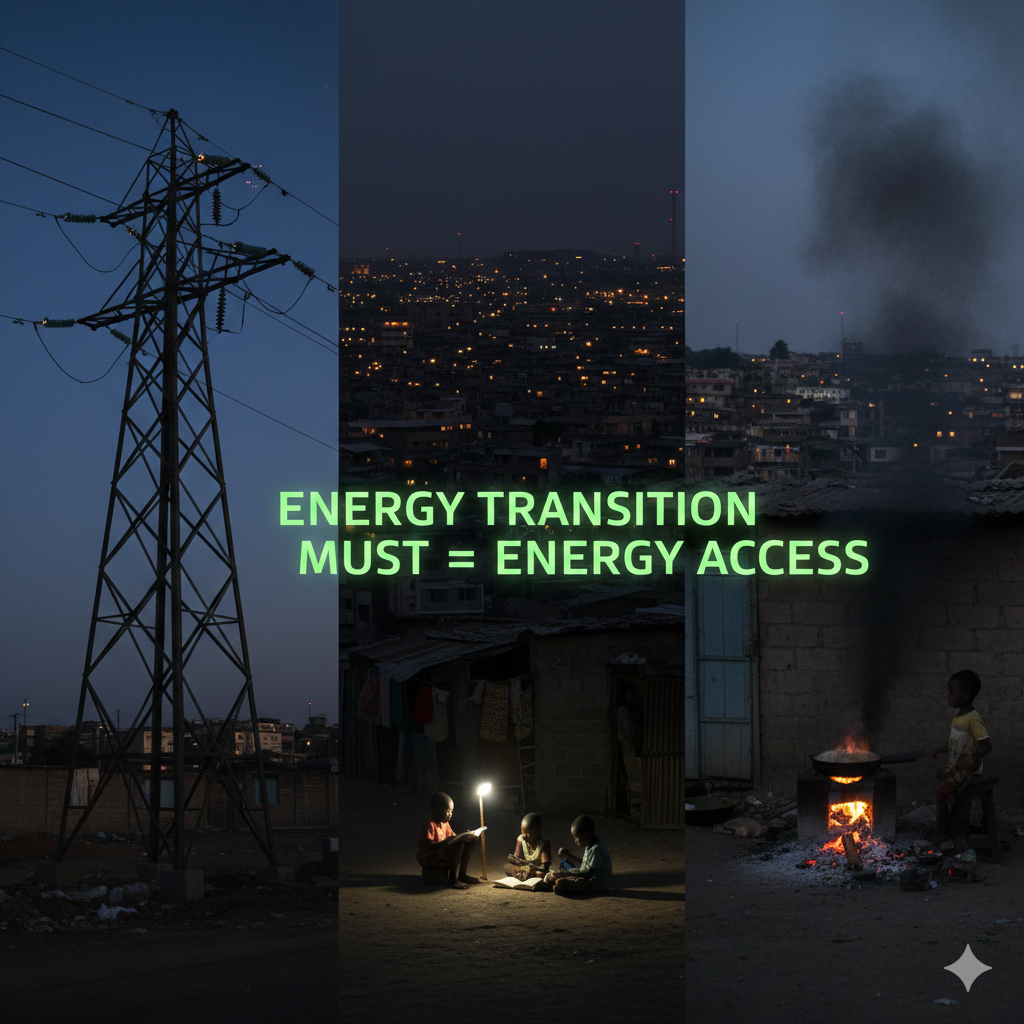

There is a phrase that has followed Africa through almost every global climate forum in recent years: “clean energy for people and planet.” And it sounds inclusive, moral and hard to argue against.

Yet across African policy circles, research institutions, and increasingly among public intellectuals, that language is being questioned, not because Africans reject clean energy, but because the words no longer reflect lived reality.

I have been in rooms where African officials nod politely as global partners speak of “accelerating the transition”, even as those same officials return home to grids that collapse, utilities that cannot pay, and millions of citizens still cooking with biomass. I have also watched African commentators push back against transition narratives that appear complete on paper and incomplete on the ground.

Africa isn’t rejecting clean energy; it is rejecting imported transition narratives that ignore infrastructure, access, and development.

What “clean energy for all” gets wrong in the African context

The phrase “clean energy for all” assumes a shared starting point. It presumes that energy systems exist, that grids function, utilities collect revenue, and that the primary challenge is decarbonisation. In much of Africa, none of these assumptions holds.

According to the International Energy Agency, nearly 600 million people in sub-Saharan Africa still lack access to electricity, while many more experience unreliable supply. In this context, energy is a development constraint and not an environmental choice.

When global narratives prioritise emissions trajectories without equal emphasis on system-building, they collapse distinct realities into a single moral frame. The result is language that sounds progressive internationally but feels detached locally.

This is why there is a growing resistance to a discourse of clean energy that treats access, reliability, and affordability as secondary considerations.

Africa’s transition challenge is structural, not rhetorical

One of the most persistent misunderstandings in global climate discourse is the belief that ambition unlocks outcomes. In the case of Africa, ambition is abundant. What is scarce is delivery capacity.

Power systems across the continent face:

- weak transmission and distribution networks,

- high technical and commercial losses,

- under-capitalised utilities, and

- politicised tariff regimes.

The World Bank has repeatedly warned that without addressing these structural issues, renewable capacity additions will fail to translate into reliable power or economic transformation. Yet much of the global transition narrative still treats Africa as a site of potential projects rather than systems in need of repair.

This disconnect shapes where finance flows, how risk is priced, and which countries are considered “ready” for transition support.

The pushback: recalibration, not rejection

African pushback against imported transition language is often misread as resistance to climate action. It isn’t. I consider it a demand for recalibration.

Across African media and policy commentary, a consistent theme has emerged: clean energy narratives must start with energy poverty, not emissions accounting. As one recent commentary in Daily Maverick put it, global clean energy ambitions will fail in Africa if they do not grapple with access, affordability, and system fragility.

This isn’t living in denial, but a reality. African voices aren’t saying “no” to clean energy. They are saying “not like this”.

Why language matters in power and policy

Language isn’t neutral. The way the energy transition is framed shapes:

- what gets funded,

- what gets regulated, and

- what gets deprioritised.

When the dominant narrative centres on speed rather than sequencing, it incentivises rapid capacity announcements over long-term system reform. When it prioritises global emissions targets over domestic access, it marginalises the political economy of energy provision.

This is why African policymakers increasingly bristle at slogans that compress complex development challenges into moral imperatives. The paradox is not rhetorical. It is lived.

Clean energy without power systems is not transition

Perhaps the most important reason Africa is rewriting the language of the energy transition is this: clean energy without functioning power systems does not deliver development.

Solar panels do not replace grids. Wind farms do not fix utilities. Batteries do not reform governance. These technologies matter, but only when embedded in systems that can transmit power, collect revenue, manage demand, and survive political cycles.

The International Energy Agency has been explicit on this point: Africa’s transition bottleneck isn’t technology availability; it is delivery infrastructure and institutional capacity, weak transmission networks, high losses, undercapitalised utilities, and fragile regulation.

Yet many global transition narratives still treat Africa as a blank canvas for clean-tech deployment, as if the primary task were simply to install capacity. This framing misunderstands the problem. Africa’s challenge isn’t adding megawatts in isolation; it is making electricity work as a system.

When clean energy is deployed into weak grids and failing utilities, it doesn’t accelerate development, but exposes structural fragility. Power is curtailed, payments are delayed, investors retreat, and citizens see little improvement in reliability.

This is why there is growing scepticism, not that anyone doubts clean energy, but because systems must come before scale. Without that sequencing, transition language rings hollow.

The credibility gap: when rhetoric outruns reality

There is also a credibility issue. African governments are asked to align with ambitious phase-out timelines even as major global players revive fossil fuel projects in the name of energy security. This inconsistency erodes trust.

Reuters reported on how renewed gas investments, including in Africa, underscore how fossil fuels remain embedded in global energy planning despite phase-out rhetoric.

When African leaders point out this contradiction, they are not being obstructionist or evasive; on the contrary, they are highlighting a trust deficit that weakens global climate cooperation.

The problem is that the rules appear unevenly applied. When energy security justifies new fossil investment in some contexts, but not others, the moral authority of universal phase-out language erodes.

For African countries, many of which still face acute energy poverty, this gap matters. It shapes whether climate commitments feel like shared responsibility or imposed constraint. And when rhetoric runs far ahead of reality, it becomes harder to mobilise domestic political support for difficult reforms. Credibility, in the end, is a prerequisite for ambition.

What Africa is actually asking for

Strip away the slogans, and Africa’s position is remarkably consistent. African policymakers, analysts, and commentators aren’t rejecting the energy transition. They are asking for it to be designed around reality rather than aspiration alone. Across countries and institutions, the core demands recur:

- transition strategies that begin with access and reliability, not just emissions targets;

- finance that prioritises system reform, grids, utilities, and regulation, rather than isolated projects;

- timelines that reflect development starting points, not uniform global averages;

- and narratives that treat energy as a public good, not merely a carbon variable.

Africa is saying, in effect: if the transition is to succeed here, it must first make electricity reliable, affordable, and politically sustainable. Only then can decarbonisation be accelerated at scale.

This position is pragmatic and reflects decades of experience with development strategies that looked convincing on paper but failed in practice because they ignored systems, institutions, and political economy.

Rewriting the narrative: from slogans to systems

The energy transition will fail in Africa if it is framed as a moral checklist rather than built as a development strategy. That is why the language is changing. African policymakers and thinkers are insisting that the transition be described and designed in terms that acknowledge:

- deep infrastructure gaps,

- limited fiscal space,

- the slow work of institutional reform, and

- the centrality of political accountability.

This shift is strategic because language shapes priorities. When transition discourse centres on targets alone, it incentivises announcements over execution. When it foregrounds systems, it forces attention onto grids, utilities, regulation, and governance, the hard, unglamorous work that determines outcomes.

By rewriting the language, Africa is asserting agency over the sequence and substance of its transition. It is moving the debate from what should happen to what must be built first.

Conclusion: naming the transition Africa actually needs

Africa isn’t rejecting clean energy; it is rejecting language that pretends clean energy is enough.

What the continent needs is a narrative that recognises that the energy transition in Africa is about building systems before optimising emissions, about development before decarbonisation metrics, and about credibility before slogans.

The transition Africa is asking for is slower, harder, and more political than much global discourse admits. It requires patience, capital, and institutional reform. It demands honesty about trade-offs and sequencing.

But this type of transition will endure because energy systems don’t change through rhetoric alone. They change when words are matched by infrastructure, institutions, and accountability.

Follow Energy Transition Africa for more updates:

![]()

![]()

Vincent Egoro is an Africa-focused energy transition analyst working at the intersection of climate justice, fossil fuel phase-out, and critical minerals governance. He brings a systems lens to how energy transitions reshape livelihoods, skills, and power across African societies. Vincent serves as Head of Africa at Resource Justice Network.