|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

On the morning the G20 released its South Africa Declaration, a senior official in Abuja joked quietly to a colleague: “Let me guess, they want us to be green, but not too green; use gas, but not too much; industrialise, but not in any way that upsets anyone.” She was half-laughing, half-tired. Because for African governments, this dance between ambition and expectation has become a familiar routine.

The G20’s latest declaration, signals a strong global push towards a green energy future. But buried between the lines, in what is said, and what is pointedly left unsaid, lies a sobering reality for Africa. The world’s richest economies want climate action at speed. Africa wants energy access, jobs and industrialisation. Gas sits at the uneasy intersection.

The G20’s message is bold, but its omissions are louder.

A green ambition without a fossil fuel exit

The declaration champions renewable energy, energy efficiency and just transitions with impressive confidence. Paragraph 25 commits the world to tripling global renewable energy capacity by 2030 and doubling energy efficiency. Paragraph 26 calls for “just, inclusive and affordable” transitions. Paragraph 28 announces the Mission 300 plan to deliver electricity to 300 million Africans by 2030.

But when it comes to fossil fuels, the engine of many African economies, the declaration takes a careful step back.

There is no explicit call for a fossil fuel phase-out.

There is no commitment to phasing down oil and gas.

Instead, the document endorses:

- “diverse pathways” for countries (Paragraph 27)

- a “technologically neutral approach” (Paragraph 27)

- support for “zero- and low-emission technologies”, including abatement (Paragraph 25)

This language, ambiguous, flexible, non-committal, keeps the door wide open for continued natural gas development. For African governments, it acts almost like a diplomatic green light.

The G20 wants ambition, yes. But it also wants stability. And stability still includes gas.

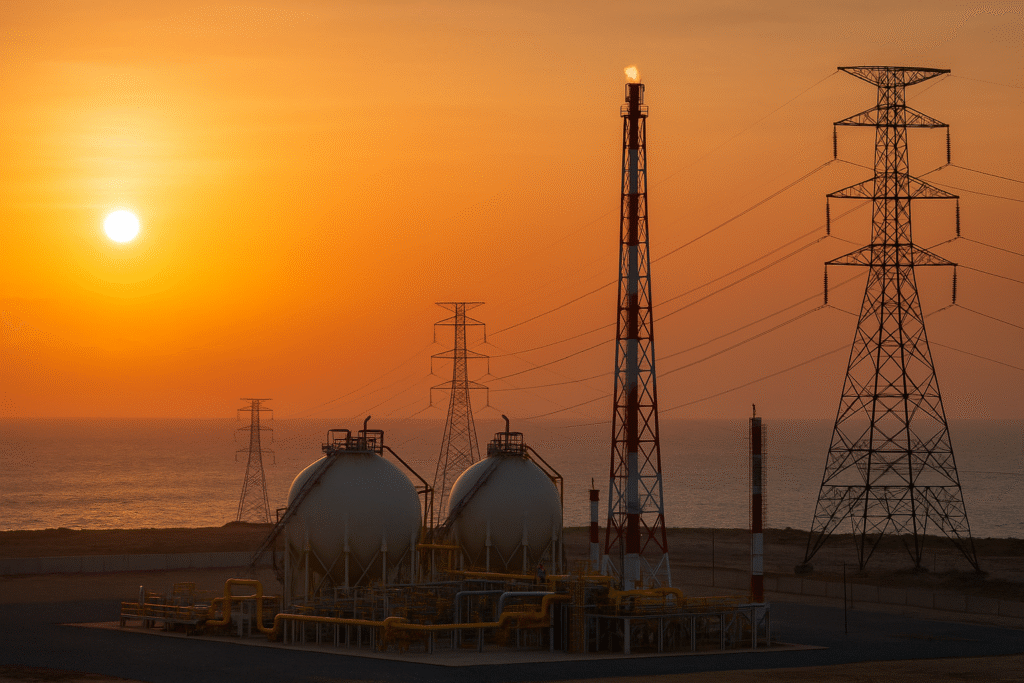

Africa’s gas moment: a development imperative

African leaders argue, often forcefully, that gas is not a luxury. It is a development necessity.

The numbers make their case.

According to the International Energy Agency,

- 600 million Africans lack electricity, and

- over 1 billion still cook with biomass,

as reaffirmed in Paragraph 23 of the G20 Declaration.

Meanwhile, Africa emits less than 4 percent of global emissions, yet its economies face the steepest development deficits:

- lowest electricity access rate (40 percent),

- lowest share of global manufacturing (under 3 percent),

- highest population growth, and

- severe infrastructure gaps.

Gas, for many African nations, is the bridge fuel that could:

- power factories,

- reduce deforestation,

- fuel fertiliser production,

- generate jobs,

- stabilise grids, and

- support growing cities while renewables scale.

Countries like Senegal, Mozambique, Côte d’Ivoire, Tanzania and Nigeria see gas as the backbone of their industrial future.

The G20 Declaration does not challenge this view directly, but it does complicate the investment pathways needed to make it real.

Investment: the fragile heart of Africa’s gas future

The declaration’s climate ambition shapes financial markets more than it shapes national sovereignty.

And here lies the quiet threat to Africa’s gas ambitions.

As G20 members strengthen their climate-finance frameworks and net-zero alignment, African gas projects increasingly struggle to secure:

- long-term financing,

- political risk insurance,

- loan guarantees,

- favourable interest rates,

- long-term off-take agreements.

The African Development Bank warns that global climate rules may restrict capital flows to new fossil fuel projects in Africa, even as Europe and Asia continue to build supply buffers for their own energy security.

The danger is clear:

Africa may be allowed to pursue gas politically, but denied the finance needed to make it economically viable.

The declaration recognises this contradiction indirectly in Paragraphs 54–60, which call for reform of the global financial architecture. But these commitments are vague, slow-moving and insufficient to alter the near-term funding reality.

This is the heart of Africa’s dilemma.

The just transition question: whose future Is being negotiated?

The G20 repeatedly stresses “just transitions” (Paragraphs 26, 30). Yet justice looks very different from Abuja than it does from Berlin or Tokyo.

For a country where 70 percent of households rely on firewood, “transitioning away from fossil fuels” is not a climate strategy, it is a public health threat.

For a country where industry barely exists, the discussion is not net-zero; it is zero.

The declaration, to its credit, places African energy poverty at the centre of global concern. Paragraph 23 lists stark realities:

- 600 million without electricity

- 1 billion without clean cooking

- 2 million premature deaths yearly from dirty cooking fumes

This is one of the strongest acknowledgements of Africa’s dual crisis, poverty and climate, we have yet seen in a G20 document.

But if justice means access, dignity and development, then Africa needs:

- massive investment in renewables,

- but also space for transition fuels,

- pathways for industrialisation,

- regional gas integration,

- and workforce development to ensure energy sovereignty.

The G20’s language supports this vision, but its financial commitments do not.

On the ground: The human reality of uncertainty

Consider the young men in Palma, northern Mozambique, who moved there years ago when Africa’s largest LNG project promised jobs, stability and economic rebirth. Construction slowed due to insecurity. Then global market volatility. Now climate-aligned investors are hesitant to return.

Or the communities in Senegal’s Saint-Louis region who believed gas revenues would improve schools, provide stable electricity and create new industries. Today, timelines shift. Finance shifts. Promises unpack slower than expectations.

These communities are not debating emissions trajectories. They are debating livelihoods.

For them, climate politics is not a diplomatic concept. It is the difference between a future and a regression.

What Africa must do, while the world decides its pace

To avoid becoming collateral in the global transition, Africa must reposition its gas strategy intelligently.

1. Embed gas within a renewable-led transition

Gas must not crowd out renewables, it must complement them.

This aligns with the IEA’s scenario that gas could support Africa’s grids while solar and wind become dominant.

2. Make the case for concessional gas financing

If the world wants Africa to transition faster, then global capital must carry part of the cost. Paragraphs 54–59 hint at this: Africa must push harder.

3. Develop regional gas corridors

Shared pipelines and LNG hubs lower costs and minimise stranded-asset risks.

4. Link all gas projects to local content and skills systems

No more export-only value chains.

No more projects without African technicians, engineers and operators.

5. Anchor gas in African sovereignty

The declaration explicitly states energy security is “fundamental to sovereignty” (Paragraph 24).

Africa should quote this line loudly.

A final reflection: Africa is not at the edges of this transtion. It is at the centre

The G20 wants a green future. Africa wants a fair one.

Between those two visions lies a negotiation about whose priorities shape the path ahead.

Africa’s gas ambitions are not an obstacle to global climate progress, they are a demand for justice, for time, for investment, for a development trajectory that does not repeat the inequalities of the past.The G20 Declaration may point the world towards a green future.

But Africa’s future will depend on whether the world allows space for development alongside decarbonisation.