The Price of Clean Energy: Why Africa Still Pays More for Sunlight Than Oil

At COP30 in Belém, amid speeches about green growth and net-zero futures, one statement is worth noting.

“For much of the developing world, high debt, high risk and a high cost of capital make renewables more expensive than fossil fuels. Without practical financial mechanisms, many countries will simply have no choice but to depend on fossil fuels if they are to develop.”

It was a reminder that Africa’s energy transition is not being held back by a shortage of sunshine or ambition. It is being held hostage by the cost of money.

Africa has some of the best solar radiation on Earth, vast wind corridors from Lake Turkana to the Namib coast, and almost a third of the world’s critical minerals. Yet building a solar farm in Kenya or Nigeria costs up to three times more in financing than building the same project in Spain or China. Renewable energy is failing, not because it cannot compete technologically with fossil fuels, but because it cannot compete financially.

A Continent Rich in Sunlight, Poor in Affordable Capital

In North Africa, solar electricity has been auctioned at prices as low as two US cents per kilowatt-hour. But in sub-Saharan Africa, developers often bid at eight to fifteen cents, four to seven times higher than in Europe. The physics are the same. The sun is the same. What changes is the price of debt.

African developers routinely borrow at interest rates between 12 and 20 percent, compared to 3 to 5 percent in Europe. A solar developer in Senegal once described it this way: “Panels don’t make renewable energy expensive. Banks do.”

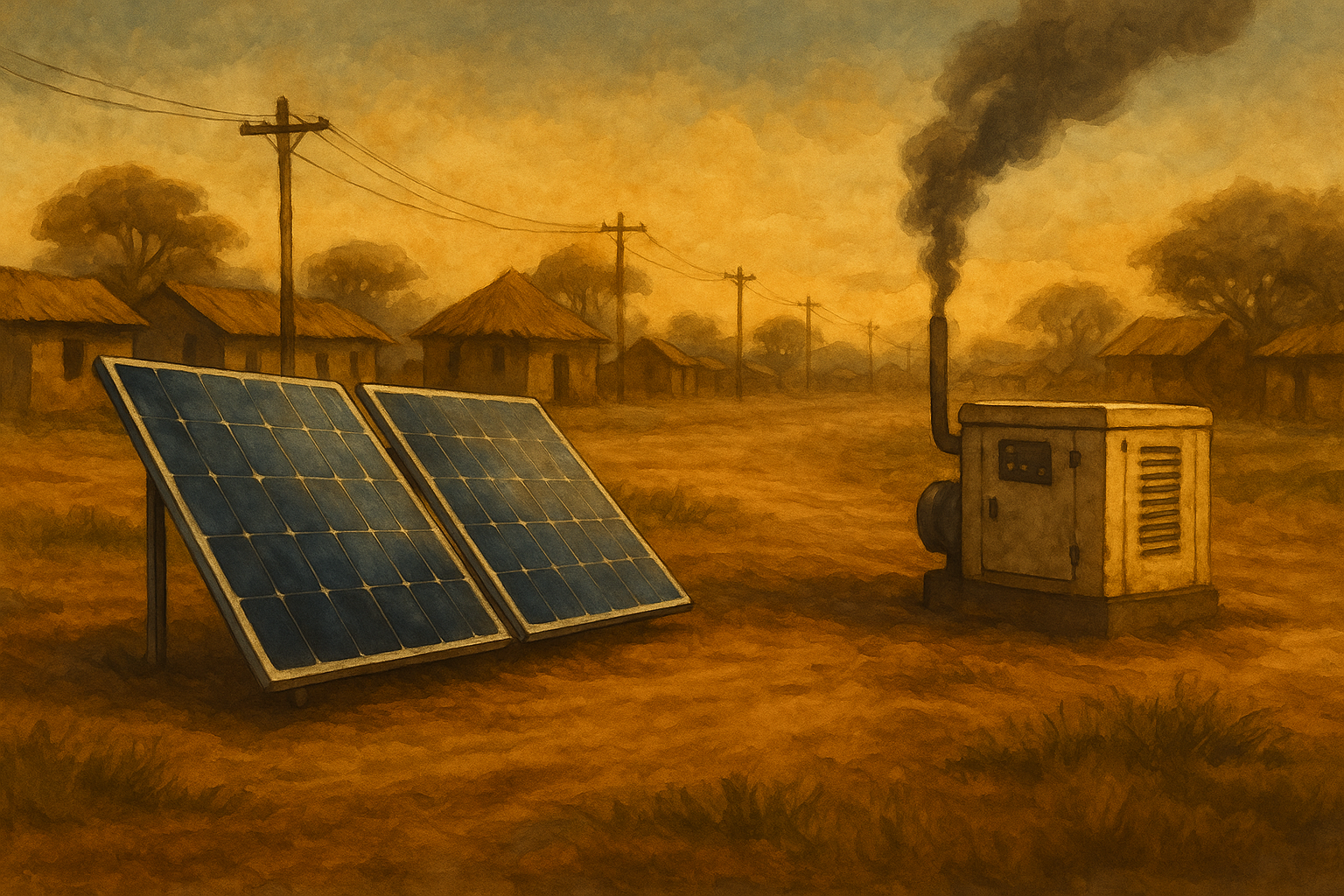

This financial penalty means that even though diesel is dirtier and more expensive to operate, it often remains the cheaper short-term option because the upfront cost is minimal and can be spread out over time.

The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimates that financing accounts for up to 50 percent of total renewable energy costs in Africa. By contrast, in Europe, financing accounts for less than 15 percent. These invisible costs, interest rates, risk premiums, currency hedging, have become Africa’s true energy bottleneck.

Debt and Subsidies: Financing the Past While Demanding the Future

While world leaders push for decarbonisation, many African governments are still paying for the fossil fuel era. In 2024, African states spent more than $85 billion on fossil fuel subsidies, according to the International Monetary Fund, a figure larger than the entire health budgets of several countries combined. Petrol subsidies in Nigeria alone consumed more public money than education, health and infrastructure budgets put together before their partial removal.

At the same time, 23 African countries are now in or near debt distress, limiting their ability to borrow for renewable investments. In economies like Ghana, Zambia and Egypt, debt service now consumes more government revenue than healthcare and energy combined.

This creates a structural paradox. Governments are told to invest in renewables, but their budgets are trapped by past debts and fossil subsidies. They are urged to scale solar, yet still pay billions to keep petrol affordable and diesel generators running.

Even when renewable projects are built, they often rely on expensive imported equipment, foreign currency loans, and private investors who demand high returns to offset perceived political and currency risks. Meanwhile, fossil fuel plants, many financed decades ago, continue operating on sunk costs.

Why the Energy Transition Is More Difficult in Africa

The argument that Africa should simply switch to solar is technically simple but financially naïve. Renewable energy is capital-intensive, meaning its costs come upfront. Fossil fuels, especially gas and diesel, spread costs over years, making them easier to finance in cash-strapped economies.

Other barriers compound the problem:

- Currency Devaluation: A 30 percent currency drop can turn a viable solar project into a loss-making venture overnight if loans are denominated in dollars.

- Utility Debt: National electricity companies in South Africa, Kenya, Ghana and Nigeria owe billions, making them unable to sign long-term renewable contracts without sovereign guarantees.

- Perceived Risk: International lenders consider African projects “high risk,” inflating borrowing costs even in politically stable nations like Botswana or Rwanda.

- Stranded Asset Fear: Investors are wary of committing to fossil fuels due to global climate pressure, yet find renewables unattractive due to weak grids and uncertain returns.

This is why a solar mini-grid operator in rural Nigeria still keeps a diesel generator nearby, not because they distrust solar, but because finance distrusts Africa.

From Lagos to Nairobi: Realities on the Ground

In Nigeria’s Nasarawa State, a solar mini-grid powers homes and shops during the day. But at night, when clouds darken the sky and batteries run low, a diesel generator hums back to life. “It’s not ideal,” the operator said, “but when banks charge 18 percent interest, diesel becomes our insurance policy.”

In Kenya, the Lake Turkana Wind Power Project, Africa’s largest, was delayed for months due to legal disputes and financing shortfalls. The turbines stood ready, but the transmission line to carry electricity to the grid took years longer to build.

In South Africa, the transition is entangled in coal debt. Eskom, the national utility, remains one of the world's largest carbon emitters, yet carries more than $24 billion in debt, much of it tied to ageing coal plants. Transitioning without financial collapse is proving politically and economically complex.

The Cost of Delay

The longer Africa remains dependent on fossil fuels, the more it risks being locked into stranded assets; oil refineries, gas pipelines and coal plants that will lose value as the world decarbonises. Yet without affordable finance, alternatives remain out of reach.

According to the African Development Bank, Africa needs $230 billion annually for energy transition until 2030. Current flows are below $30 billion. Of that, less than 2 percent of global renewable investment reaches the continent, even though it holds 17 percent of the world's population.

What Needs to Change

A new financial architecture, not new technology, will determine whether Africa transitions or remains fossil-dependent.

1. Finance in local currencies, not dollars.

Afreximbank and the African Development Bank are piloting local-currency green bonds that shield solar and wind developers from currency shocks. These must scale.

2. Redirect fossil fuel subsidies to clean energy.

Even reallocating 10 percent of Africa’s fossil subsidy budget could fund more than 5,000 community-owned solar mini-grids a year.

3. Make Just Energy Transition Partnerships work in reality, not rhetoric.

South Africa secured an $8.5 billion climate finance deal. Yet less than 5 percent has been disbursed. Funds must be faster, simpler, and tied to economic inclusion, not consultant reports.

4. Invest in power grids, not only generation.

Without grid expansion and battery storage, renewable projects cannot deliver power where it is most needed.5. Electrify people, not only infrastructure.

As we previously reported in our article on responsible minerals finance, technology without people is an empty promise. Skills: engineers, electricians, community technicians, must be funded as seriously as solar panels.

“Panels don’t make renewable energy expensive. Banks do.”

Conclusion: Choosing the Future or Financing the Past

Africa does not lack sunlight, wind or ambition. It lacks affordable capital. The energy transition will not be decided by how many solar panels are built, but by who controls the money used to build them.

If global finance continues to make clean energy more expensive than oil, Africa will remain trapped, not by resources, but by interest rates.

The world cannot demand a transition while funding the status quo. And Africa cannot afford to wait for perfect conditions. The choice is clear: reform finance or repeat history.